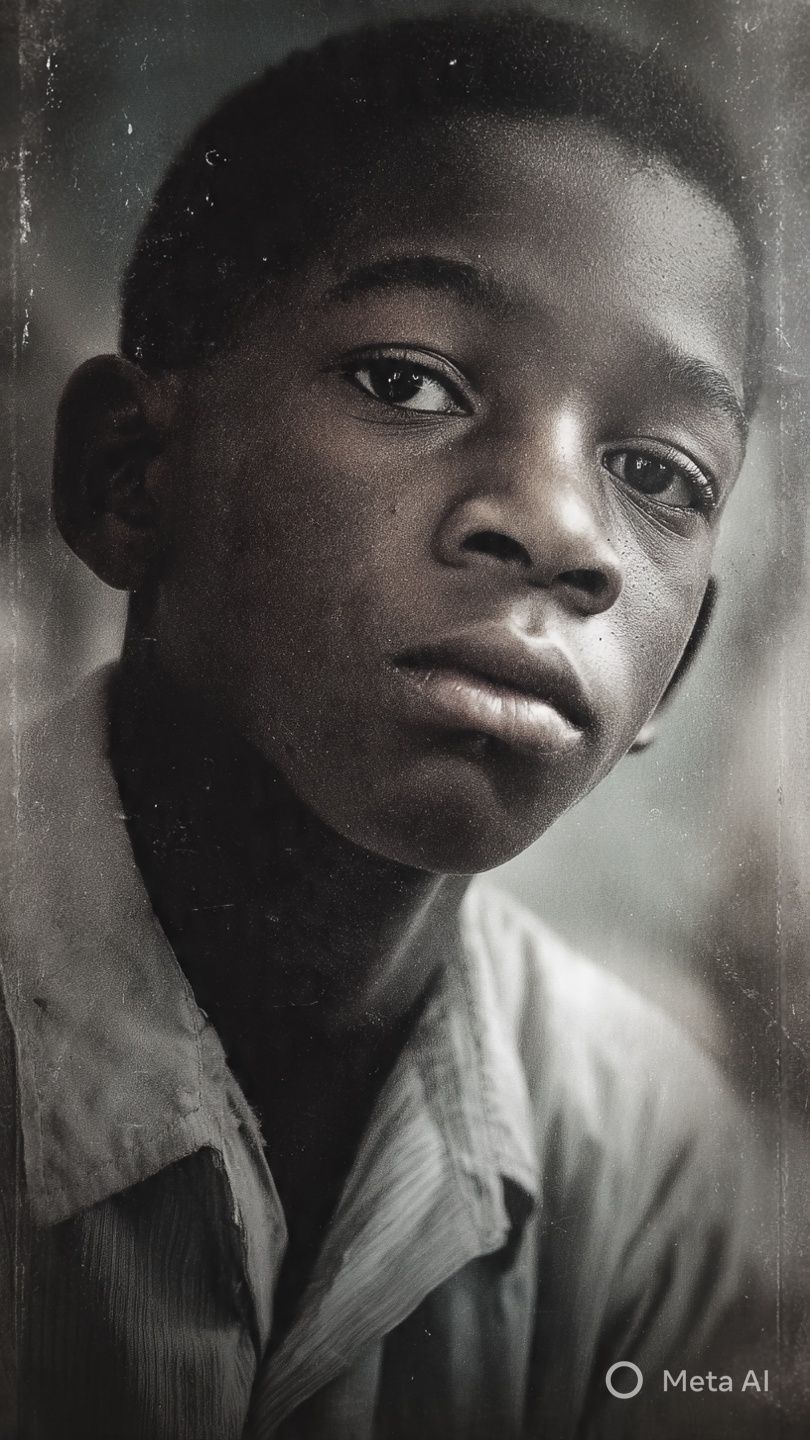

In a small, segregated town in South Carolina, called Alcolu, the year 1944 was supposed to be like any other. But for a 14-year-old boy named George Stinney Jr., it became the year his life ended in the cruelest way imaginable.

George was just a kid, living on the "wrong" side of the railroad tracks that divided his town, when tragedy struck. Two young white girls were found murdered, and almost immediately, fingers pointed at George. He was Black, and in that time and place, that was often all it took.

Imagine being 14, scared and alone, with no parents or lawyer to stand by you, as grown men in authority interrogate you. That's what happened to George. They claimed he confessed, but there was no proof, no signed paper, just their word against a terrified boy's.

His "trial" was a horrifying farce. It barely lasted two hours, a whirlwind of injustice in a courtroom filled with white faces – no one who looked like him, no one who truly saw him. The jury took just ten minutes to decide his fate. Ten minutes. For a life.

The sentence was death by electric chair. The world moved so fast around him, a blur of fear and prejudice. His family, terrified themselves, had to flee their home. They couldn't even be there for him in those final, desperate moments.

On June 16, 1944, George Stinney Jr., a child who still played with marbles, walked to the execution chamber. He was too small for the chair, so they stacked books for him to sit on. The mask that covered his face fell off when the electricity surged, revealing his wide, tear-filled eyes. He was just 14 years old.

It took 70 years for justice to finally whisper his name, long after his small body was buried. In 2014, a judge finally overturned his conviction, acknowledging the monstrous injustice, the coerced confession, and the utter failure of a legal system poisoned by racism. But it couldn't bring George back. His story remains a haunting scar, a reminder of a life unjustly taken, and the profound sadness of what was lost.